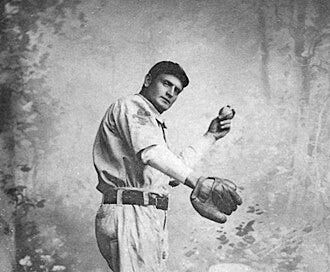

Drunk, Distracted, and Dominant: The Rube Waddell Story

A fire-truck-chasing, alligator-wrestling, strikeout machine—this is baseball’s strangest legend.

It’s the bottom of the ninth. Two outs. The crowd leans in as Rube Waddell winds up—then drops his glove, points to the outfield, and takes off in a full sprint. A fire engine tears down the street beyond the left field wall. The batter just stares. No swing. No pitch. Just Rube, too unpredictable to fit the story—and too good to be left out of it.

The Curious Case of Rube

George Edward “Rube” Waddell was born on Friday the 13th—October 13, 1876—in Bradford, Pennsylvania. The date tracks. He was a strange kid from the jump. Legend says that at age three, he wandered off for several days and was found at a local fire station, playing with the hoses. His lifelong obsession with fire trucks started there.

School didn’t hold his attention. Instead, he worked on the family farm, chucking rocks at birds to build up his arm. He took jobs in mining and drilling. Wrestled semi-pro. Strength and oddity came naturally. Direction did not.

Until baseball.

Too Good to Ignore, Too Weird to Manage

By his teens, Waddell was lighting up town leagues across Pennsylvania. In 1897, he signed his first professional contract with the Louisville Colonels for $500—roughly $19,000 today. But the majors didn’t quite know what to do with him.

He’d vanish for weeks. Get distracted by dogs in the stands. Wander off mid-game if a fire engine rolled past. One offseason, he joined a traveling circus and wrestled alligators. Another time, he went fishing in full uniform—during a game.

Fans caught on. They waved puppies and shiny objects to throw him off. And sometimes, it worked.

He was a spectacle. He was a mess. But above all—he was electric.

The Sousepaw Who Could Deal

Waddell was also a lifelong alcoholic. He reportedly blew his entire first signing bonus on a bender. The Sporting News dubbed him a “sousepaw”—a drunken twist on the baseball term “southpaw.”

He missed games. Showed up drunk. Took bartending shifts between starts. He brawled with teammates, fans, and sometimes himself. He clashed with every manager he had.

And yet, the man kept getting chances.

Because despite everything—despite himself—he was a generational talent. In 1900, he posted a 2.37 ERA with the Pittsburgh Pirates. A year later, he won 26 games in the minors. But it was in Philadelphia, under the calm command of Connie Mack, where Rube truly hit his stride.

Connie Mack’s Wildest Weapon

Connie Mack was the only manager who ever figured Waddell out. Where others tried to cage the chaos, Mack embraced it. He let Rube be Rube—because when he pitched, he was untouchable.

Waddell joined the Philadelphia Athletics in 1902 and instantly became the league’s top strikeout artist. He led the American League in strikeouts six seasons in a row. In 1904, he fanned 349 batters—a record that stood for over 60 years.

This wasn’t in the age of radar guns and year-round training. This was a time when pitchers pitched hungover and hitters almost never struck out. Waddell threw a fastball that looked like it came out of a cannon and a curve that folded hitters in half. Nobody could touch him.

And crowds couldn’t get enough. He was baseball’s first true spectacle—equal parts ace and attraction.

The Downside of the Sideshow

But the fame didn’t sober him up. It just gave him a bigger stage to be Rube.

The stakes got higher, but the behavior stayed the same. He missed team trains. Ignored curfews. Got into fights on road trips and forgot pitching assignments altogether. His talent bought him a longer leash than most, but even that started to fray. Teammates grew tired. Managers lost patience. Front offices couldn’t count on him to make it through a full season without disappearing—or blowing up.

Eventually, even Connie Mack had to let go. Waddell was sent to the St. Louis Browns, where the talent was still there, but the magic was wearing thin. The innings dwindled, the headlines quieted, and the league that once tolerated his chaos slowly moved on without him.

By 1910, Waddell’s major league career was over.

A Strange, Heroic Exit

In 1913, Kentucky was hit by a catastrophic flood. Waddell—no longer famous, no longer employed—showed up to help. He spent days stacking sandbags to protect homes and rescue trapped residents. It was a flash of real heroism from a man most had written off as a clown.

But the flood soaked him through. He caught pneumonia and never truly recovered. Tuberculosis followed. And on April 1, 1914—April Fools’ Day, no less—Rube Waddell died in a sanitarium in San Antonio, Texas. He was 37.

He was born on Friday the 13th and died on April Fool’s Day—which feels about right. If anyone was destined to live between a punchline and a superstition, it was Rube.

Shortly after Waddell’s death, sportswriter Roy J. Dunlap reminisced about Waddell’s final professional game

“Those 2,000 or more fans who sat on the bleachers or in the grand stand and doubled up with laughter at the jester’s antics probably never will forget that eventful day. Perhaps Rube knew it would be his last fling. The more one thinks of his work in the twelve grueling innings the more he is impressed that Rube felt the intuition of an invisible fate. Rube ever has been fate’s plaything. Fate molded him into a jester, and has criss-crossed his eventful life since.”

Waddell’s life never followed a clean arc. He wasn’t built for legacy, and he didn’t chase it. But even in the final stretch—sick, forgotten, long past his prime—he still showed up when people needed help. Maybe that’s the part that matters most. Behind all the chaos and comedy was a man who, for all his flaws, never stopped surprising people. Even at the end.

The Hall of Fame’s Most Unlikely Resident

Rube Waddell left behind a stat line that still pops off the page.

193 wins. A 2.16 career ERA. 261 complete games. 50 shutouts.

And from 1902 to 1907, he led the American League in strikeouts six years in a row—at a time when strikeouts weren’t even a big part of the game. The man once fanned 349 batters in a single season, a record that stood until Sandy Koufax broke it in 1965. He did it all without modern training, without offseason programs, and often without knowing where he’d be the next day.

He was chaos in a uniform, and still one of the most dominant arms of his era.

In 1946, more than three decades after his death, the Hall of Fame finally called his name. Maybe it was overdue. Maybe it was a mercy. Either way, it was proof that, for all his unpredictability, Rube Waddell couldn’t be denied.

Connie Mack, the man who managed him at his peak, once said:

“There was never a pitcher like Rube Waddell. He had more stuff than any pitcher I ever saw. He had everything but a sense of responsibility.”

That just about nails it.

Why You Probably Never Heard of Him

Rube Waddell doesn’t fit the mold. He wasn’t disciplined. He didn’t care about image. He didn’t build a legacy—he just lived, brilliantly and recklessly, until it all burned out.

Baseball history tends to favor legends who, whether or not they lived clean lives, fit a certain mold: dominant on the field, beloved by the press, and marketable to the masses. Ruth could party hard, but he still showed up and smashed home runs. Waddell, on the other hand, vanished to wrestle alligators and chase fire trucks.

He was too wild to mythologize. Too inconsistent to protect. Too strange to simplify.

And so, like a lot of people who live too far outside the lines, he slowly faded from the spotlight.

Most have never heard of him.

Those who have—never forget.